As far as we know, until 1876 no specific result was obtained concerning the topology of nonsingular real plane curves of an arbitrary degree. The year 1876 is often considered as the beginning of the topological study of real algebraic curves. Prior to that topological properties were not separated from other geometric properties, which are more subtle and could keep geometers busy with curves of a few lower degrees.

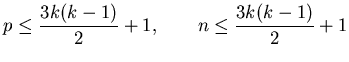

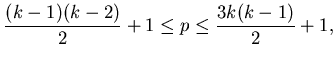

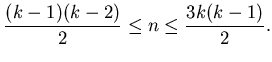

In 1876 A. Harnack published a paper [5] where he found an exact

upper bound for the number of components for a curve of a given degree.

Harnack proved that the number of components of a real plane projective

curve of degree ![]() is at most

is at most

![]() . On the other

hand, for any natural number

. On the other

hand, for any natural number ![]() he constructed a nonsingular real

projective curve of degree

he constructed a nonsingular real

projective curve of degree ![]() with

with

![]() components,

which shows that his estimate cannot be improved without introducing

new ingredients.

components,

which shows that his estimate cannot be improved without introducing

new ingredients.

It was D. Hilbert who made the first attempt to study systematically topology of nonsingular real plane algebraic curves. The first difficult special problems he met were related to curves of degree 6.

Hilbert suggested that from a topological viewpoint the most

interesting are the curves having the maximal number

![]() of components among curves of a given degree

of components among curves of a given degree

![]() . Hilbert's guess was strongly confirmed by the whole

subsequent development of the field. Now, following I. Petrovsky, these

curves are called M-curves.

. Hilbert's guess was strongly confirmed by the whole

subsequent development of the field. Now, following I. Petrovsky, these

curves are called M-curves.

Hilbert succeeded in constructing M-curves of degree ![]() with mutual

position of components different from the ones realized by Harnack.

However he realized only one new real scheme of degree 6. See Figure

4 where the real schemes of Harnack's and Hilbert's curves of

degree 6 are shown. Hilbert conjectured that these are the only real

schemes realizable by M-curves of degree 6 and for a long time claimed

that he had a (long) proof of this conjecture. Even being false (it was

disproved by D. A. Gudkov in 1969, who constructed a curve with the real

scheme shown in Figure 5) this conjecture captured the essence

of what in the 30-th and 70-th became the core of the theory.

with mutual

position of components different from the ones realized by Harnack.

However he realized only one new real scheme of degree 6. See Figure

4 where the real schemes of Harnack's and Hilbert's curves of

degree 6 are shown. Hilbert conjectured that these are the only real

schemes realizable by M-curves of degree 6 and for a long time claimed

that he had a (long) proof of this conjecture. Even being false (it was

disproved by D. A. Gudkov in 1969, who constructed a curve with the real

scheme shown in Figure 5) this conjecture captured the essence

of what in the 30-th and 70-th became the core of the theory.

In fact, Hilbert invented a method which allows one to answer all questions on the topology of curves of degree 6. It involves a detailed analysis of singular curves which could be obtained from a given nonsingular one. The method required complicated fragments of singularity theory, which had not been elaborated at the time of Hilbert. It was only in the sixties that this project was completely realized. A complete table of real schemes of curves of degree 6 was obtained by Gudkov.

Coming back to Hilbert, we should mention his famous list of problems [7]. He included in the list, as a part of the sixteenth problem, a general question on topology of real algebraic varieties and more special questions like the problem on the mutual position of components of a plane curve of degree 6.

One curious aspect of this problem seems to be its number in the list. The number sixteen plays a very special role in the topology of real algebraic varieties. It is difficult to believe that Hilbert was aware of that. It became clear only in the beginning of seventies (see Rokhlin's paper ``Congruences modulo 16 in Hilbert's sixteenth problem'' [15]). Nonetheless, sixteen was the number assigned by Hilbert to the problem.

In 1906 V. Ragsdale [14] made a remarkable attempt to analyze Harnack's and Hilbert's constructions to guess new restrictions on topology of curves. To a great extent the success of her analysis was due to the right choice of parameters of a real scheme.

Ragsdale suggested considering separately the case of

curves of even degree ![]() . Each connected component of the set of

real points of a curve of even degree is an oval (i. e., positioned in

. Each connected component of the set of

real points of a curve of even degree is an oval (i. e., positioned in

![]() two-sidedly and divides

two-sidedly and divides

![]() into two parts).

An oval of a curve is called even (resp. odd) if it lies

inside of an even (resp. odd) number of other ovals of this curve.

The number of even ovals of a curve is denoted by

into two parts).

An oval of a curve is called even (resp. odd) if it lies

inside of an even (resp. odd) number of other ovals of this curve.

The number of even ovals of a curve is denoted by ![]() ,

the number of odd ovals by

,

the number of odd ovals by ![]() .

.

It was Ragsdale who

suggested distinguishing even and odd ovals. Ragsdale

provided good reasons why one should pay special attention to ![]() and

and

![]() . A curve of an even degree divides the plane

. A curve of an even degree divides the plane

![]() into two pieces

with a common boundary

into two pieces

with a common boundary

![]() (these pieces are the subsets

of

(these pieces are the subsets

of

![]() where a polynomial defining the curve takes

positive and negative values, respectively). One of these pieces is

nonorientable, it is denoted by

where a polynomial defining the curve takes

positive and negative values, respectively). One of these pieces is

nonorientable, it is denoted by

![]() . The other one

is denoted by

. The other one

is denoted by

![]() .

The numbers

.

The numbers ![]() and

and ![]() are

the fundamental topological characteristics of

are

the fundamental topological characteristics of

![]() and

and

![]() .

Namely,

.

Namely, ![]() is the number of connected components of

is the number of connected components of

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() is the number of connected components of

is the number of connected components of

![]() (exactly one component of

(exactly one component of

![]() is nonorientable, so

is nonorientable, so ![]() is the number of orientable components of

is the number of orientable components of

![]() ).

Ragsdale singled out also the difference

).

Ragsdale singled out also the difference ![]() motivating this

by the fact that it is the Euler characteristic of

motivating this

by the fact that it is the Euler characteristic of

![]() .

It is amazing that essentially these considerations were

stated in a paper in 1906!

.

It is amazing that essentially these considerations were

stated in a paper in 1906!

|

|

|

This motivated the following conjecture.

Writing cautiously, Ragsdale formulated also weaker conjectures. About thirty years later I. G. Petrovsky [11], [12] proved one of these weaker conjectures.

It is clear from [11] and [12], that Petrovsky was not familiar with Ragsdale's paper. But his proof runs along the lines indicated by Ragsdale. He also reduced the problem to estimates of the Euler characteristic of the pencil curves, but he went further: he proved these estimates using the Euler-Jacobi formula.

Petrovsky also formulated conjectures about the upper bounds for ![]() and

and ![]() . His conjecture about

. His conjecture about ![]() was more cautious (by 1).

was more cautious (by 1).

Both the Ragsdale Conjecture formulated above and its version stated by

Petrovsky [12] are wrong. However they stood for a rather long

time: the Ragsdale Conjecture for ![]() was disproved by O. Y. Viro

[16] in 1979. Viro's disproof looked rather like an

improvement of the conjecture, since in the counter-examples

was disproved by O. Y. Viro

[16] in 1979. Viro's disproof looked rather like an

improvement of the conjecture, since in the counter-examples

![]() . In 1993 Ragsdale-Petrovsky bounds were

disproven by a considerable margin in I. V. Itenberg

[8]: in Itenberg's counter-examples the difference between

. In 1993 Ragsdale-Petrovsky bounds were

disproven by a considerable margin in I. V. Itenberg

[8]: in Itenberg's counter-examples the difference between ![]() (or

(or ![]() ) and

) and

![]() is a quadratic function of

is a quadratic function of ![]() (see

below).

(see

below).

The numbers ![]() and

and ![]() introduced by Ragsdale occur in many of the

prohibitions that were subsequently discovered. While giving full credit to

Ragsdale for her insight, we must also say that, if she had looked more

carefully at the experimental data available to her, she should have been able

to find some of these prohibitions. For example, it is not clear what stopped

her from making the conjectures which were made by Gudkov [2]

in the late 1960's. In particular, the experimental data could suggest

the formulation of the Gudkov-Rokhlin congruence [15]: for

any M-curve of even degree

introduced by Ragsdale occur in many of the

prohibitions that were subsequently discovered. While giving full credit to

Ragsdale for her insight, we must also say that, if she had looked more

carefully at the experimental data available to her, she should have been able

to find some of these prohibitions. For example, it is not clear what stopped

her from making the conjectures which were made by Gudkov [2]

in the late 1960's. In particular, the experimental data could suggest

the formulation of the Gudkov-Rokhlin congruence [15]: for

any M-curve of even degree ![]()

Maybe mathematicians trying to conjecture restrictions on some integer should keep this case in mind as evidence that restrictions can have not only the shape of an inequality, but a congruence. Proof of these Gudkov's conjectures initiated by Arnold [1] and completed by Rokhlin [15], Kharlamov [9], Gudkov and Krakhnov [3] marked the beginning of the most recent stage in the development of the topology of real algebraic curves.

Which of Ragsdale's questions are still open now? The inequalities